Writing up IoTmark - 1 of 2

I went to last Friday’s IoTMark follow-up event from last summer's Open IoT Definition, partly because I figured I’d learn a lot, also because whether I like it or not, the evolution of the Internet of Things (IoT) is something I feel I should have a handle on as someone working in tech.

https://twitter.com/mrchrisadams/status/972009776518381569

The day was more productive than I had expected it to be, and I learned loads - but before I could put together a writeup, it seemed worth giving some more context here if this was new to you. There's another post where I do the write up of the day itself.

My background, and disclaimers

I am definitely not an IoT expert. I write this from the perspective who is paid to write code, but also paid to run workshops, and help product development teams work more effectively together.The one system I put into production in 2009 with my first company that you might describe as vaguely IoT-y was a system where we were inferring utilisation by co-workers in a couple of co-working spaces, based on detecting people's devices connected to wifi.

We then monitored energy used in a building, and then tracked the energy mix on the national grid to work out the carbon footprint per person per hour of the space.

[gallery ids="2896,2895,2897" type="rectangular"]

The idea was to help the owner make an argument that you could have a greener office, by shaping demand and making better use of the space available. I'm happy to chat about the lessons learned here, but that's another post.

It was some of my first python programming, it was buggy as hell, a source of incredible stress for me, and commercially ruinous for my company, but I learned about failure modes, security, and all the weird ways things can fail, at the worst possible time. In fact, it was enough for me to flee from anything to do with hardware, for years. As such, there may be errors, and I might get terminology wrong - please contact me direct if you see any, and I'll change them.

I share this to give some background of where I'm coming from, if my viewpoint seems different to yours.

The background of the Open IoT events and IoTMark

In 2012 - the Open Internet Of Things Assembly

In 2012, along with a bunch of other nerds, I went to the Open IoT Definition event on 17th June 2012, at the Google Campus in Shoreditch, organised by Alexandra Deschamps-Sonsino, and ended up at a fascinating, if somewhat chaotic event. Over the day, 60-70 people ended up forming groups to talk about various aspects of how IoT were affecting our lives, how the incentives seemed to reward all wrong kinds of behaviour, and how we feel a more humane version of this might look.This culminated in something like 50 different people, trying to use google docs to simultaneously author a sort of bill of rights, the Open Internet of Things Definition, to encapsulate this.

https://twitter.com/mrchrisadams/status/214382405778276352?ref_src=twsrc%5Etfw&ref_url=http%3A%2F%2Fstorify.com%2FPepeBorras%2Fopent-iot-assembly

Amazingly, there's still a storify available of the day that does a fairly good job of capturing what it all felt like.

The day felt nice, and I met loads of really interesting people, but I'd be lying if I said we all left the day, and rebuilt everything we did along the principles written up in that Open IoT document.

Fast forward 2017 - The Internet of Things Mark

Last year, I heard from Alex and Usman, letting me know that they were planning to do a follow-up event, and asking whether I'd be interested in coming back to help moderate one of the sessions.The goal of the day was to come up with a kind of trustmark for IoT products, and we needed to agree on what the trustmark stood for, before we could go through the process of registering trademarks, and all the necessary legal bits.

The venue they had found was London Zoo, and it dovetailed (sorry) nicely with a good friend's birthday.

So, I booked a train from Berlin to London and headed over for June 17th 2017 - 5 years to the day of the last event.

What, someone did something with those principles?

One of the things that really surprised me at the event, was that some larger companies had been paying attention to the work going into these principles as a way to carve out a competitive advantage.

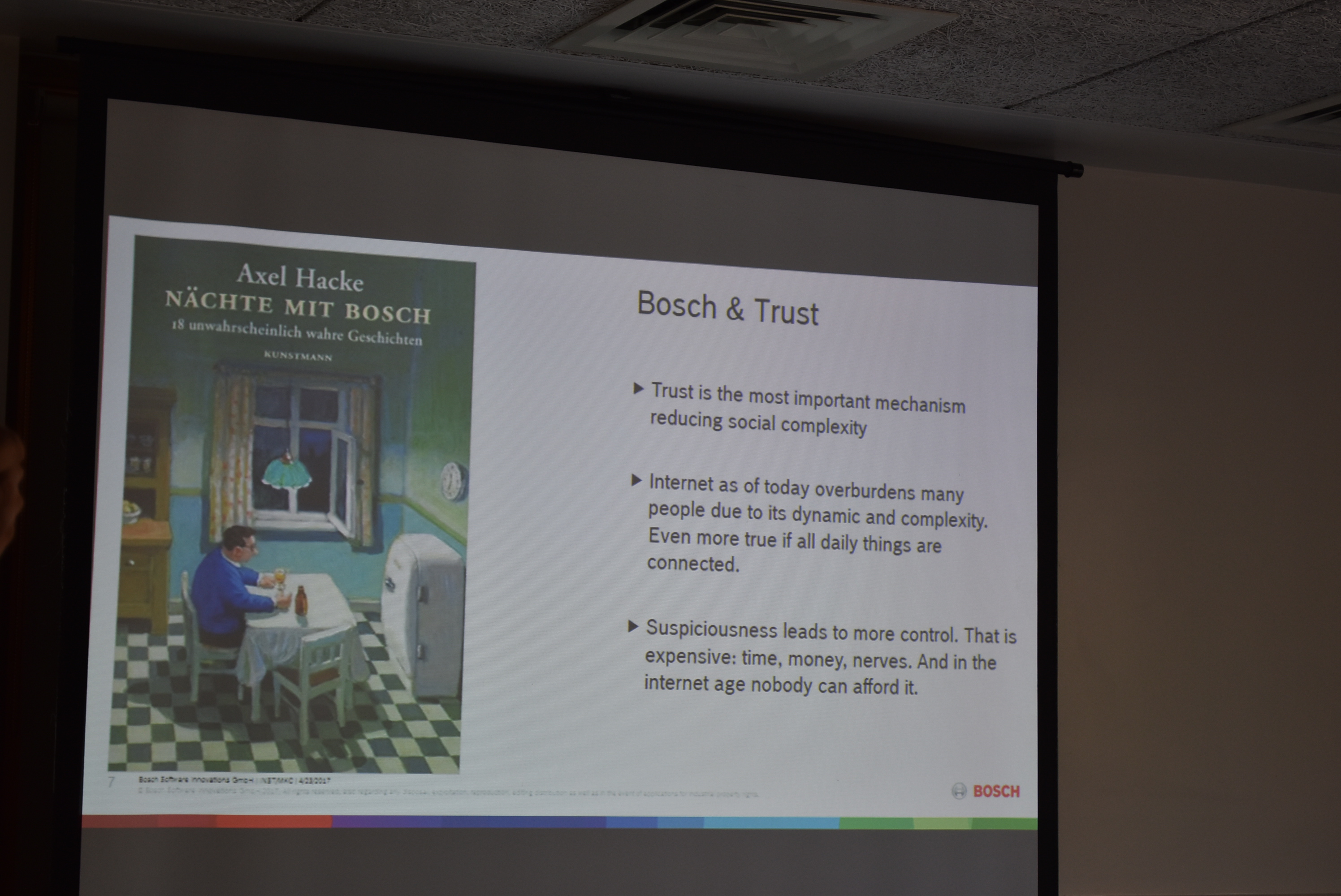

In particular, we saw Stefan Ferber from Bosch talking about many of the same principles we had written about, and how they were applying them in their work.

In particular, he was talking about the benefits of trust when thinking about IoT - optimising for trust as response to an ever more complex world.

If I can trust the service or the product I'm using, rather than having an adversarial relationship (i.e. like I might with many low cost flight airlines, or ad-tech providers, or much of retail banking in the US, etc.), then it follows that I'm more likely to want to use offerings from the company making it over others.

Moderating the life cycle group

Shortly after some intros, we ended up splitting into interest groups, and I ended up helping moderate one of the sessions around the environmental and life-cycle aspects of IoT.In our group, we had quite a wide mix of people, from young founders building VC-backed IoT startups, to people from the Restart Project talking about repair and design for remanufacture, and embedded programming specialists concerned with the end of life of IoT hardware.

We were looking at planned obsolescence, end of life support - for example, when hardware is literally embedded in your house, and you sell your house, but can't transfer ownership of the devices, you have new kinds of problems we haven’t really had to deal with before.

Or when your phone works, but through software update policy is left dangerously vulnerable to hackers, to the extent it's irresponsible to put data on it, you have the kinds of problems we were exploring that effectively make it unusable for many of the common use-cases you might associate with a typical smartphone.

We also looked into the embodied carbon, and fairness of the supply chains - where the minerals like coltan come from that make up your computer chips, and the conditions in which they're made, and where hardware is assembled.

So, all the easy problems, then.

Our goal was to come up with some principles we could all agree to in our group, and would be prepared follow in this absolute discussion minefield of topics. As you imagine, getting someone in a VC-backed hardware startup set up for hyper growth to find common ground with a design for repair campaigner is not easy, but we ended up with a few principles we could take the the final session of the day.

One day we will learn

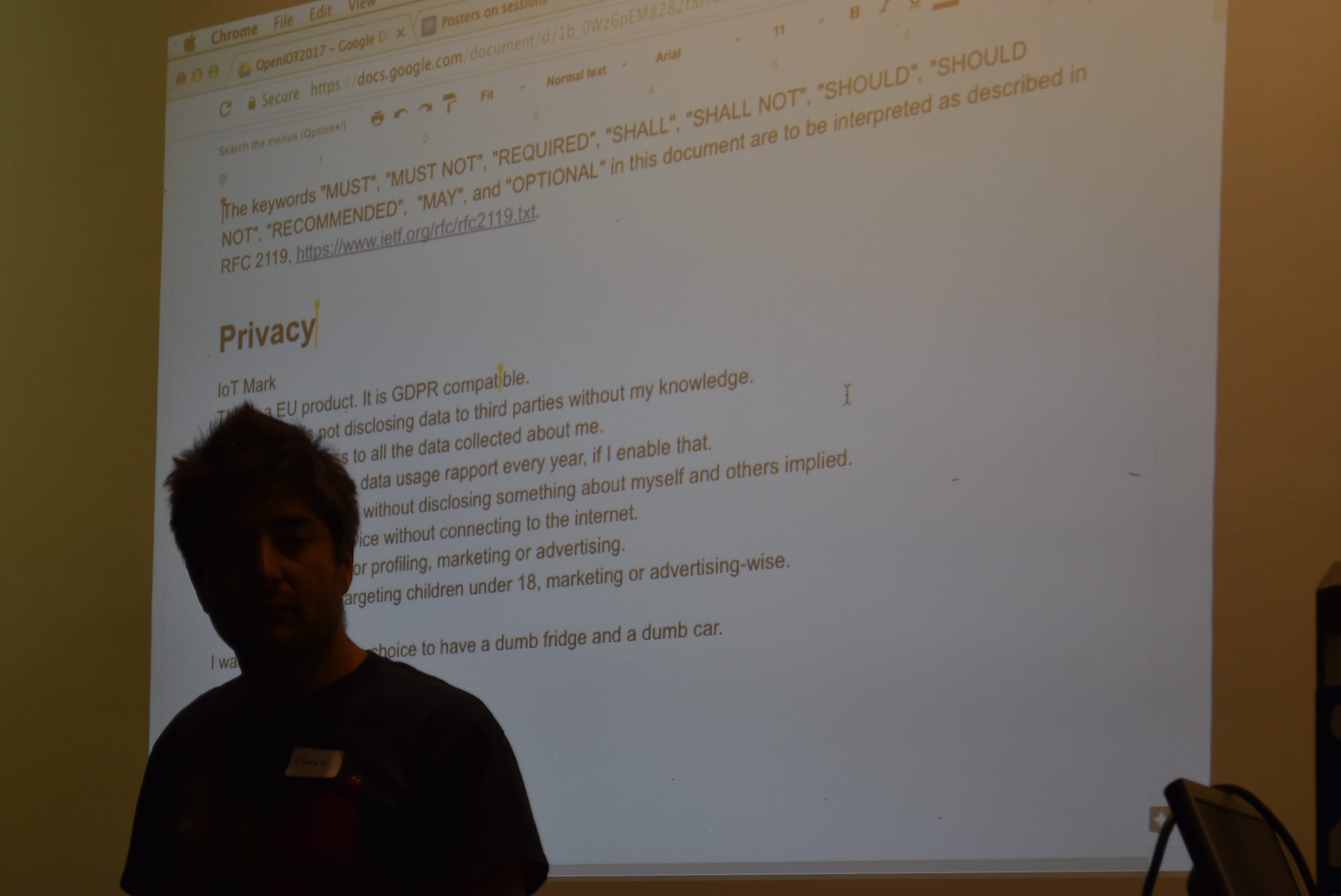

[caption id="attachment_2902" align="alignnone" width="2992"] Usman, once again, trying to get 60 people to agree in a google document[/caption]

Usman, once again, trying to get 60 people to agree in a google document[/caption]

And once again, we tried to get 60 people to agree to principles, but this time, we were trying to get something more concrete to put on a product, so it was even harder to find consensus.

Even after the back and forth within my group, we found that loads of the stuff we had settled on as uncontroversial had others pushing back hard - so we ended up with much more watered down set of ideas in the lifecycle section.

The Open IoTMark RFC

Like the last event, the culmination was a group of people, essentially yelling at poor Usman, as he and other people tried to write a document to capture all the ideas in the principles.But this time round, given the number of engineers in the audience, someone came up with idea of describing these principles using the normative language you'd see from the IETF.org, with very specific, precise meanings applied to the words like MUST, SHALL, SHOULD, and so on.

I'll be honest - this entire process was exhausting and not very satisfying.

This shouldn't be news though, and it wasn't isn't a reflection on Usman's skill as a facilitator - I think it's very hard to avoid in cases like this.

As you move from principles you care about when it's not your job to own the supply chain and deliver the returns an investor is expecting, to actually having to publicly say you're prepared adopt these principles, of course you're going to get push-back.

That said, Usman pushed on, and before we had to leave, we somehow ended up with a document that if everyone wasn't happy with, they were prepared to co-sign it.

And that's the background. Here's the actual write up of the day.