Planet friendly web development with Python - a transcript

Over the last few months, I've spoken at a few conferences and meet-ups around Europe about what I'm calling the "Planet-Friendly Design" or "Planet-Friendly Web Development", to a mixture of UX focussed audiences, and developers. The slide decks I have used for each conference are available online at speakerdeck (mainly because I've been updating decks and what I say each time).

Somewhat inspired by Ana Balica's transcript post of from her keynote for Pycon CZ last year , and Maciej Cegłowski long form talk/essay hybrid pages, I'm also experimenting with putting the talk on my blog here, to make it easier to digest. I'll add the video once it's online.

Here we go…

Planet Friendly Web Development with Python

Hello. My name is Chris Adams.

I started out working with Django in 2008, but over the last ten years I’ve also worked as a designer, a sysadmin, a product manager, a UX consultant, and and a user researcher, on various environmentally minded projects and startups. I currently live and work in Berlin, I booked a train down with Loco2, and I’m working with Thermondo in Germany.

Over this time, I’ve been thinking a fair amount about how what we do as developers relates to the wider discussion about the environment and climate change taking place.

My aim today is to provide you with some context for how what we do fits into this wider picture, and share a mental model for thinking about building apps with this in mind, along with some examples of how this relates to your work.

I'll be mentioning carbon dioxide a few times today, so I’m going to start with a quick reminder on the greenhouse effect. Here’s more or less how it works:

Sunlight hits earth.

When energy from the sun hits Earth, some of it ends up warming the planet, and some bounces back off into space. What's special about Earth though is that it has large enough quantities of certain gases within the atmosphere, primarily CO2, to bounce some of the energy back to Earth again.

This energy warms up the planet, so we refer to these gases as greenhouse gases, and the phenomenon as the greenhouse effect.

So, this greenhouse effect has been very useful to us. It's made life possible in the first place.

Over the last 100 years or so, largely as a result of human activity, we’ve ended up with greater levels of greenhouse gases, and in particular CO2, in the atmosphere.

More CO2 results in a more powerful greenhouse effect, resulting in more energy in the system, and a warmer world.

While warmer world sounds nice, it turns out that the reality is less nice.

The reality is more extreme weather events, more drought, more destruction to vital ecosystems we rely on, and in general, problems of the kind that scientists describe as existential threats, and ones that can only really be solved by collective action.

So, since the mid-nineties, we (and by we, I mean the countries making up the United Nations) have been meeting every year for a series of huge, long meetings, to agree on what to do about this, the aforementioned existential threat to our civilisation.

And finally, after 21 goes at getting it right, in 2015 in Paris - more or less everyone agreed that we definitely want to limit climate change, and we also want to aim for to less than 2 degrees of global warming in total.

This effectively created a ceiling on the total amount of greenhouse gases we can emit as a planet - a carbon budget, so if we want to stay inside this budget, our emissions need to go a bit like this (short video of showing the emissions drop off from Bret Viktor's essay What can a technologist do about climate change? A personal view)

Getting an agreement like the one in Paris was quite impressive, but what’s even more amazing, is that people are actually following through with the agreement, and changing how their economies work.

According to the International Energy Agency, 2017 is the third year where global emissions didn't increase, but the global economy still grew.

So, we’re seeing a decoupling of economic growth from emissions - and we can now point to this happening in America and China, the two biggest emitters as they move away from coal, while their economies continue to grow.

That said though, before we start feeling too proud of ourselves, we do need a sense of perspective.

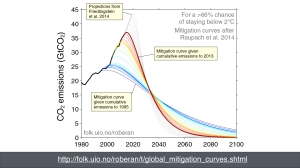

Because it’s taken this long to reach a turning point, as a civilisation, we need to reduce our emissions much more aggressively than a few years ago if we want to stay within 2 degrees. The blue line here shows what we needed to do in 1995, and the red line onwards shows how much faster emissions need to fall now as a result of our inaction.

Okay, so we have established that:

- we can change our economies

- we have a lot of work to do

- we need to do it fast

Where do we start?

(image is from Robbie Andrew's blogpost It's getting harder and harder to limit ourselves to 2°C)

This Sankey diagram from 2010 shows a rough breakdown of global emissions by sector and gas. The bit on the left shows the key sources of emissions, the middle bit shows emissions by sector responsible for them, and the bit on the right shows which gases are responsible for the Greenhouse effect.

Agriculture is about 7%, and road transport is about 10%, like deforestation (filed euphemistically as “land use change” here), and energy generation is about 13%.

Flying, which is one we hear a lot about only shows up as a between 1 and 2 percent of global emissions. IT doesn’t even show up - it’s just lumped in with the other categories.

And this is a key thing when talking about climate change and the environment, if you woke up tomorrow and thought "I HAVE to do something important about climate change" you wouldn't start with changing how you design your websites.

There are important discussions to have about our diets, (i.e. how much meat we eat, how keep homes warm or cool, how we travel around the world by car or fly, and so on).

However, I’m not here to talk about that, as it’s far beyond the scope of the time I have. Instead, I’m here to talk about our impact when we build things online.

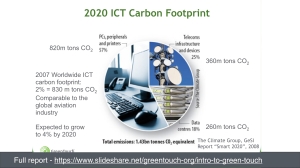

This deck, citing the Climate Groups Smart 2020 report shows IT at around 2% of planetary CO2 emissions in 2007 - about the same as aviation.

Remember how much power generation (i.e. electricity) contributed to emissions in the last graph? Well, as an industry, we’re getting pretty power hungry. I live in Germany, currently the 4th largest economy on Earth. Deutsche Telekom is the 3rd largest consumer of electricity in the country.

And in three years time, as an industry, we’re predicted to be responsible for twice the emissions as aviation.

So we may have started as a small part of emissions, but we're growing fast. And as web developers, while we might not have direct control over deforestation, we do have rather more control over how we might use data centres and infrastructure for shipping our bits to our users.

As I said before, I’ve been trying to come up with a mental model to help me take this stuff into account when I’m building sites or apps, and I’m going to share it with you today.

And I’m doing it because I think there’s a lot of overlap between what’s good environmentally, and what’s good practice for building digital products and services.

I also think that if you want to bring about the change we need, framing it in positive terms, like being awesome at your profession is a better approach than trying to shame people into action.

So, I’ve grouped this mental model into three main areas: Your Platform, Your Packets, and Your Process, drawing on existing communities of practice, that don’t always speak to each other:

For Your Platform, we borrow ideas from software engineering, and technical architecture, and the devops movement.

For Your Packets we borrow ideas from Web Performance Optimisation.

For Your Process - we borrow ideas from the Lean UX movement, and continuous delivery, but there isn't really time today to cover it in much depth. There’s a link to a 45 minute talk I gave in November at the end of this deck though.

When it comes to servers you control you can think of two things to think about. who your providers are, and how you provision your computing power.

The first part covers how the electricity powering your servers is generated. This is probably where you have the most direct control.

A few years back, if you wanted to run your apps on green power, you’d either need to run them in Iceland where almost everything runs on clean geothermal power, or with a number of small providers either who weren’t too reliable, or had limited product offerings. You’re less likely to make a trade-off between ‘green’ and ‘effective’ these days, and in Europe at least, the two real cloud giants, Amazon and Google claim to run on renewable energy, or be working towards it. So if you’re using these, and you’re running servers in Europe, you’ve already made a decision that reduces the carbon footprint of your app, considerably.

If you’re not, there are other things that determine how much CO2 is emitted on behalf of your app. Specifically how efficiently you use the capacity you’ve paid for, from your provider.

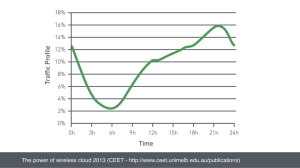

This graph from the CEET report "power of the wireless cloud" here for example shows the typical usage patterns of traffic across the internet in a given area over the day. We’re all asleep, then we start work, then we go home and watch netflix.

For many of us, we’re so used to paying for compute by the month, that we don’t really think too much about how the capacity we’ve reserved matches up to when our users are awake - we often just think about making sure there’s always enough headroom (reserved capacity) to meet the top end of traffic we expect.

But if we’re thinking about the environmental impact of this unused computing capacity, then I think that’s a missed opportunity - it feels a little bit like leaving the office lights on at work when you go home.

For the longest time, because provisioning servers has been slow and a hassle, it has made sense to just leave the lights on, because the cost of managing this outweighs any savings you might make.

(quote from Adrian Cockrofts' medium piece Evolution of Business Logic from Monoliths through Microservices, to Functions)

But as we’ve started to use services more than servers, this has changed. When we shift to use PaaS, we trade a higher unit cost of compute for the greater ease of management of these resources. If we’re looking at this through our planet friendly web lens, we might care about scaling down during periods of low use, so we burn less compute, and therefore less CO2.

Increasingly you can do this automatically in response to heuristics about load and response time, but if that sounds a bit like voodoo to you, you can also just do it on a timer, by looking at previous usage patterns. I’ll touch on this later.

There are other models though. When you pay per response like with FaaS, you don’t really pay for reserved capacity in the same way at all. This changes how you think about redundancy and failover (you aren’t paying to have redundant servers in some high availability configuration anymore), and scaling, versioning of APIs… all kinds of things.

Instead you pay per 100 milliseconds you spend serving a request, and you pay for the RAM you use. So, if you can improve code to servicing the same request twice as fast, you see the cost halve.

Similarly, if you can serve the same request in half the memory footprint, you’ve halved it again.

In many cases, less CPU burned means less money spent and also means less CO2 released.

Into performance optimisation? Check you out captain planet, you’ll go far, in this new world!

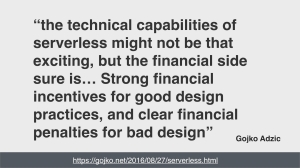

(Quote from https://gojko.net/2016/08/27/serverless.html)

So, you might be wondering why this talk is feeling like a talk about optimisation, rather than the environment. This is what I mean by there being a lot of overlap between things that reduce how much CO2 we emit into the atmosphere, and good engineering practices.

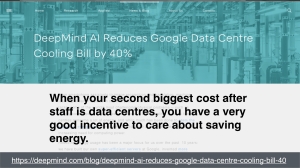

Google and Amazon don’t necessarily care about saving energy because they’re warm fuzzy companies. They do it because it’s good business sense, and they work at a scale where the incentives to save energy are proportionally greater, and can use more sophisticated techniques. In the example above, Google bought Deepmind an AI company, for hundreds of millions of dollars, then deployed the AI to work out the most efficient way to save electricity in their datacentres. This reduced the amount of CO2 emitted, but also saved them a huge amount of money.

So, planet friendly can be wallet friendly -

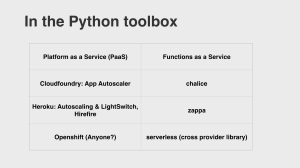

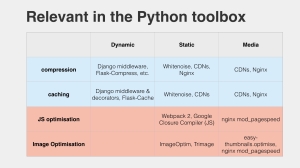

The choices in this table outline some of your options, for platforms, services, or libraries, that you might want to look into if any of this has caught your attention so far.

So, we’ve covered servers you have control over, and how using green energy, and using your compute resources effectively has an effect on how much CO2 you emit.

You typically need to send data to your users though - if the previous section was Your Platform, think go this as Your Packets.

When a request leaves your servers, you don’t have much control over how it routes through the web to reach a user.

This is a feature of the internet, and is usually a good thing.

However, you don’t have control over how green the rest of the infrastructure you rely on is. So, sending data can result in wildly differing amounts of CO2 emissions too, depending on where those servers are.

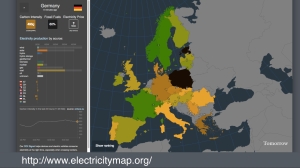

This map shows how green the electricity is around Europe, based on what kind of power is used to generate it. The further from green the colour is the more CO2 intensive the energy is.

You can see that France is geeen because it's full of nukes.

The Scandinavian states are green because they have lots of hydro power.

Germany is brown because while it has lots of solar, it also has lots of coal.

And Poland has loads of coal, so it’s really dirty power.

We’ve covered how the energy mix in a country is likely to affect our impact. As this quote from a recent Center for Energy Efficient Telecommunications report suggests, the type of connection used also affects the CO2 emissions of sending data.

The recent switch to 4G has meant that while we get data faster, it’s also much more energy intensive. This means our CO2 emissions increase here, as a greater amount of our traffic moves to mobile.

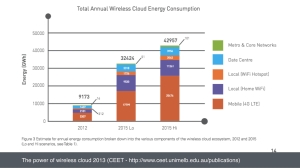

This graph from the Center for Energy Efficient Telecommunications shows predicted growth in energy usage back in 2012, and the impact of switching to 4G.

Even in the best case scenario, this showed at least 3x increase in power usage - for mobile - 4G transmission alone is larger than ALL the energy use from a three years earlier.

Compounded by this, we can see an obesity crisis in webpage size. There’s a clear direction of travel here - ever larger pages, sent over more energy intensive connections - and it’s pretty much the opposite of what we’d want from a CO2 emissions perspective.

I’m trying avoid being too ‘doom and gloom’ here, but folks - the average webpage is bigger than the game Doom was when it was first release now.

So, what can we do?

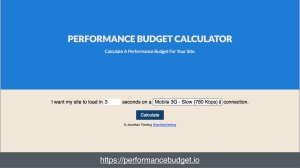

One technique the web performance community has used to help fight this bloat, has been the use of performance budgets in designs. While the goal here is a better user experience and a fast loading site, it also turns out to be pretty planet-friendly too, as it reduces the amount of data being sent, and therefore energy used, and therefore CO2 being chucked into the atmosphere.

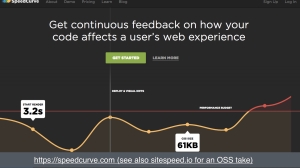

Whats also cool is that just like how we have continuous integration to check our tests work, you’re now seeing tools like Speedcurve, or CalibreApp, that work like Continous Integration on for page and performance budgets on key pages on your production site. So we have a tool to guard against this now.

What’s more these allow for lots of other clever uses. For example, I know that U-switch, a uk energy switching company, used this to benchmark their site against competitors, but also to get their home page down to around 600k in size, and there are many, many studies correlating increased web performance and sales from amazon, easy and so on.

If you want an open source option, I suggest you look at sitespeed.io too.

When we’re talking about the packets of data you send, I’ve found it useful to think of your packets in terms lossy changes you might make, and lossless changes.

We often make ‘lossy’ trade-offs in what we send to people - you deliberately reduce image quality and dimensions, or omit unused code, to deliver a faster loading, better user experience.

For example, when a user gets sent lots of stuff they won’t use, or appreciate in a web page now, it’s a waste. They might just want a nice dropdown menu, but they get masses of javascript and a whole bootstrap’s worth of CSS, regardless of whether they want it or not. Why do this when we can just send the css and js we need? There’s loads of interesting work going on in this area, which I’ll refer to in more detail in a bit.

If the previous idea is lossy, you might think of another category, where compression and caching fit in, as a more ‘lossless’ approach.

When I gzip or minify files, I don’t lose information, or remove functionality, but amount of data sent is smaller. And when I’m use caching or a CDN, by choosing to not send data you already have, I still end up with less data to deliver, without losing information.

So, we've looked at two ways how we affect the environmental impact of sending packets to our users. Coincidentally, they almost always result in a better user experience, as pages end up loading faster, and we often end up with us, and our users paying less for bandwidth.

If there is one takeaway I really want you to take from this talk, it’s this: making a site work better for the planet is pretty much the SAME THING as making it work better for users. So, the chances are, many of you in this room have already spent years becoming black belts in planet-friendly web-ninjutsu. Hear that Neo? You already know kung fu.

Remember those scary graphs I mentioned at the beginning of this talk, and how basically every industry needs to change if we want to stand a chance at staying inside that planetary budget of 2 degrees? As professional developers, we’ll need to know what those changes look like inside our industry too - especially given that IT is being seen as one of the best tools we have for building a greener, more sustainable future.

I aimed in this talk to give you a better understanding about where what we do as developers fits into the global picture, and how some of the stuff you might already be doing has an effect on the environmental impact of the sites and apps you create.

So I hope in your day to day jobs, you’ll see how things you already know how to do can help make the sites you build more planet-friendly, as well as cost less, and provide a better user experience. You might do it because you feel strongly about the environment like me, but you might do it because you like looking awesome in front of your boss. The key thing as developers we don’t really need to choose - for us they’re the same thing!

So, I’ll end this talk by with a quote from one of my favourite childhood cartoons - the power is yours.

Okay, that was it. When I gave this talk at Djangocon, there were about 300-350 people in the audience. Pycon Italia was closer to 70, and I believe Pycon Czech had about 100.

I'm tempted to just be done with it and create a proper talk page for this, as while Wordpress is easy to use, for getting something out the door, if I'm writing about this subject, it would be good to y'know, practice what I'm preaching more, and use some of the techniques I refer to in the talk.

If you have questions, feel free to drop me a line of leave a question in the comments (I'll help me think through the ideas better), and I'll try to address it below.